Bruyn's Housefly

My nonfiction essay—Bruyn’s Housefly—was recently published in The Deadlands, a monthly speculative fiction magazine about the other realms, the ends we face here, and the beginnings we find elsewhere. The piece opens with a discussion about these two works by the great German Renaissance painter Barthel Bruyn the Elder, which were painted on opposing sides of the same canvas:

My piece uses an art history lesson about why Bruyn put that grim Vanitas image on the back of a charming bridal portrait as a launching point for a deeply personal narrative about loss, grieving, and anxiety. I’m very proud of this work and, if you’d like, you can read the whole thing for free at the link below:

Decoding the Images

As usual, my piece in The Deadlands is accompanied by a sequence of Vanitas still life images. I’d like to share those here and unpack their symbolism in a bit more detail than I was able to in the essay.

Vanitas with Bones and Insects, by Neal Auch

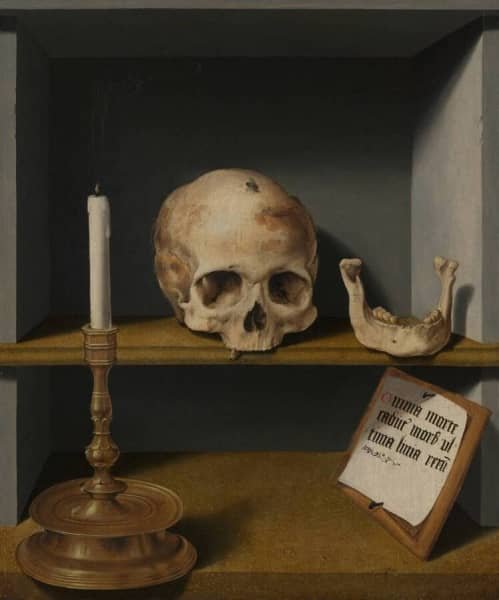

These images are very much an homage to Bruyn’s 1524 Vanitas painting (above). Bruyn’s image is one of the earliest historical examples of a Vanitas still life, and it is admirable in the simplicity of its arrangement. Bruyn uses only 4 elements to tell his story: a skull, a housefly, an extinguished candle, and scroll bearing the motto “Everything passes with death; death is the ultimate limit of everything.“ In my own images, I have appropriated these key motifs: each photograph in my series is based around re-iterating and re-arranging bones, candles, and insects.

Vanitas with Bones and Insects, by Neal Auch

As I explain in the published essay, this process of iteration and re-arrangement was an exercise in uncovering and enriching meaning. In some images the dead insects represent death, decay, and finality—in much the same way that Bruyn probably intended his housefly. In other images I replaced the fly with cicada husks, suggesting a more hopeful interpretation of an otherwise grim scene, and nodding at the possibility of renewal and rebirth.

Samuel Beckett has been a great influence on my development as an artist and, in this process or re-arrangement and re-iteration, I take a lot of inspiration from his prose, which often featured the same few phrases being repeated and twisted and permuted throughout the work. This idea is perhaps most explicit in the play Krapp’s Last Tape, although you can see a similar technique at work in more famous works like Endgame or Waiting for Godot. But perhaps my favourite example is Beckett’s wonder poetic novel How It Is where, as Hugh Kenner puts it, “a few dozen expressions permuted with deliberate redundancy accumulate meaning even as they are emptied of it.“ It is very much my hope that the handful of elements in these images can serve a similar purpose.

Vanitas with Bones and Insects, by Neal Auch

While I generally pride myself in creating images that reward scrutiny, I think that this series in particular works best if one can really pay attention to the small details. The placement of the insects in each scene is intended as a kind of mini-arrangement—a still life within a still life. To highlight those details I’ve included here some blow-up images.

Vanitas with Bones and Insects, by Neal Auch (detail inserted)

As is always the case in my still life work, the geometry of these arrangements is intended to convey a sense of instability and uncertainty. Because Vanitas art deals with death and transience, I am always trying to convey a sense that the arrangements themselves are transient—the slightest breeze threatens to topple the whole arrangement from the table.

The candles here are also reminders of instability: life, like the candle, can be extinguished in an instant. It is very much for the same reason that the cups and bowls in these images so often appear tipped over or dangling off the table ledge—I am hoping to convey a sense of precarious balance.

In my series I also have added a key element that are is present in Bruyn’s original Vanitas: the dead flowers. Flowers in still life would normally be presented in full bloom and used to represent the transience of earthly beauty. I often prefer to use flowers that are already dead, in part because I like to draw attention to the unlikely ways in which floral beauty persists even after death, but also because I find such haunting similarity between the textures of dead flowers and the other withered husks in my work: the insect carapaces and dry bones.

Vanitas with Bones and Insects, by Neal Auch

Anway, that’s all I have to say about these images! Please do check out the full article if you’re interested; I think it adds a lot in terms of meaning and emotional resonance.

In my next mailing I’ll share some new images and discuss a true story about housing, poverty, chronic disease, and medical assistance in dying. The narrative is very sad, very fascinating, and fraught with ethical complexity, so stay tuned for that. Also, as always, if you know someone who might be interested in this kind of thing please do encourage them to subscribe. I’m trying to build up my mailing list as a way of sharing nuanced and grim art without living in fear of the arbitrary whims of social media algorithms, and every new subscriber really does help me out.